I’ve been delinquent in firing off these newsletters. The truth is that I’ve been at my limit, probably a bit beyond it.

A book takes a lot of work not only on the front end (the proposing, selling, researching, writing, and editing of the thing) but on the back end too. Altogether, I’ve probably done thirty or so talks and interviews, including a lecture, various themed interviews (the Mexican view, bordering through a constitutional lens, the extreme right), and have hit seven different cities, with more still coming.

That’s on top of my day job, the novel I’m polishing, and a few big freelance pieces I’ve got in the fire.

So I’m offering here a few stray thoughts that have been tendriling out of all these book talks and interviews.

Gaza

“First denial, then blocking, shrinking, silencing, hemming in.”

That’s Edward Said’s tidy formulation for what Israeli settlers did to dispossess and displace Palestinians in the middle of last century, it’s what they’re doing to them now in Gaza, and it’s the same series of steps other colonial nations have followed to wrest control of a land and then erect border barriers as means of control, exploitation, and sometimes annihilation.

I’ve been thinking of that quote — from The Question of Palestine — a lot recently, and am finding it widely applicable. Not only does it pertain to, I’d argue, all bordering, but it applies to narratives about bordering.

The makeshift and now broken pier, the taunting calls to let in more aid via sea, land, or air drop — what it does is reinforce the border.

I’m not saying that the militarized border is the cause of the ongoing siege and mass murder, but that understanding the roots of the hemming in of Gaza is key to understanding the apartheid regime. Said is right to start with denial in his parsing of colonialism: denial of a people’s (Palestinians’, Native Americans, Aboriginal, any of the people exposed to the disease of imperial statecrafting) existence and history on the land, denial of their humanity, and then the blocking of them, the shrinking, the silencing, and the hemming in.

Here’s how that hemming is currently playing out: the only remotely viable exit from Gaza today is through Rafah, and the only real way out, if you’re a Palestinian in Gaza, is by paying an Egyptian company that charges anywhere from $5,000 to $15,000 per person. A close Palestinian friend of mine recently paid $8,000 each for two of his family members to cross into Egypt. That money went to fixers working for Hala, a for-profit border-brokering company whose owners have direct ties to the son of Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, the president of Egypt.

There’s hardly a more essentializing example of how borders function: filtering human beings by passport and price-gouging refugees fleeing genocide.

And yet, widening the doors isn’t the answer. That’s because opening selectively permeable doors in a border, again, reinforces that same border.

It must also be said that there’s no mitigating or turning down the volume on genocide. There’s only stopping it.

Media

Besides Gaza, another issue that has come up a lot in my talks is the rachitic discourse around borders and bordering. Of course, there are principled and nuanced conversations happening in some circles, but overall, the national conversation about borders and immigration is about a sophisticated as something a peckish toddler might have with a stressed-out parent at the end of a long day.

In other words, my book could have been called not The Case for Open Borders, but the Case for Opening the Conversation About Borders.

Terrible title, but an earnest plea.

I’ve found from my many recent talks about borders that some people not only reject arguments I and others make for the freedom of movement, but they refuse to even hear them. They don’t believe basic facts.

It’s hard to say why that’s the case, but my strong hunch is that a lot of it comes down to three big issues around the topic of migration: narrative framing, media literacy, and fear.

The problem with narrative framing begins with historical amnesia: a basic historical naïveté that lets people look at something happening today and see it as unprecedented when clearly it is not. Such ahistorical positions lock people into a status quo bias, letting people see a contingent reality (a militarized border) as a natural or inevitable phenomenon. I spend a lot of time in my book going through exactly how today’s borders developed the way they did, revealing two key points:

People have always moved

Borders (as we know them today) have not always been

I think the Left (by which I mean, in this case, people defending the right to mobility) needs to be more imaginative in the way we critique border regimes and how we organize society, but first we need the opposite of imagination: we need to bring the discourse down from the oxygen-starved heights of rhetorical excess and accusation and ground it in reality.

We do not have open borders, the government is not handing out gift cards or free flights, and non-citizens are not voting in federal elections. None of what is happening at the US southern border amounts to an invasion.

If you have evidence to counter any of those claims, bring it, but naked insistence does not a fact make.

Until we can agree on some of the above and other basic truths, until we return to the same plane of reality, the Left is going to exhaust itself trying to play defense to and deflate fear-mongering fabulation. And defense is not how you move the political needle, and it’s definitely not how you bring about justice or equal rights.

My point, in the book and now, is that borders were not only relatively recently created, they are in a constant act of creation. If it weren’t for billions of dollars of funding, constant and expensive construction and remediation of physical infrastructure, an active and enormous corps of border guards, plus the constant fueling of “the need” to border, the strips of land along today’s borders would — very quickly — look very different.

Which brings me to my conclusion: thrown-bones and piecemeal policy tweaks are not and will not solve the crises being lived out along the world’s borderlines.

We need facts, analysis, and principles. To end, here’s a simple principle I discuss and build off of in my book: there shouldn’t be different laws and rights for different groups of people based on where they were born.

Jaguars and sundry

What am I reading now? Working hard on wrapping my head around coyotaje. More from me on that in a few months.

Here are two recent articles I was thrilled to write.

-An essay in New York Review of Books of John Vaillant’s Fire Weather and Jeff Goodell’s The Heat Will Kill You First. Both books are disturbing and yet important reads.

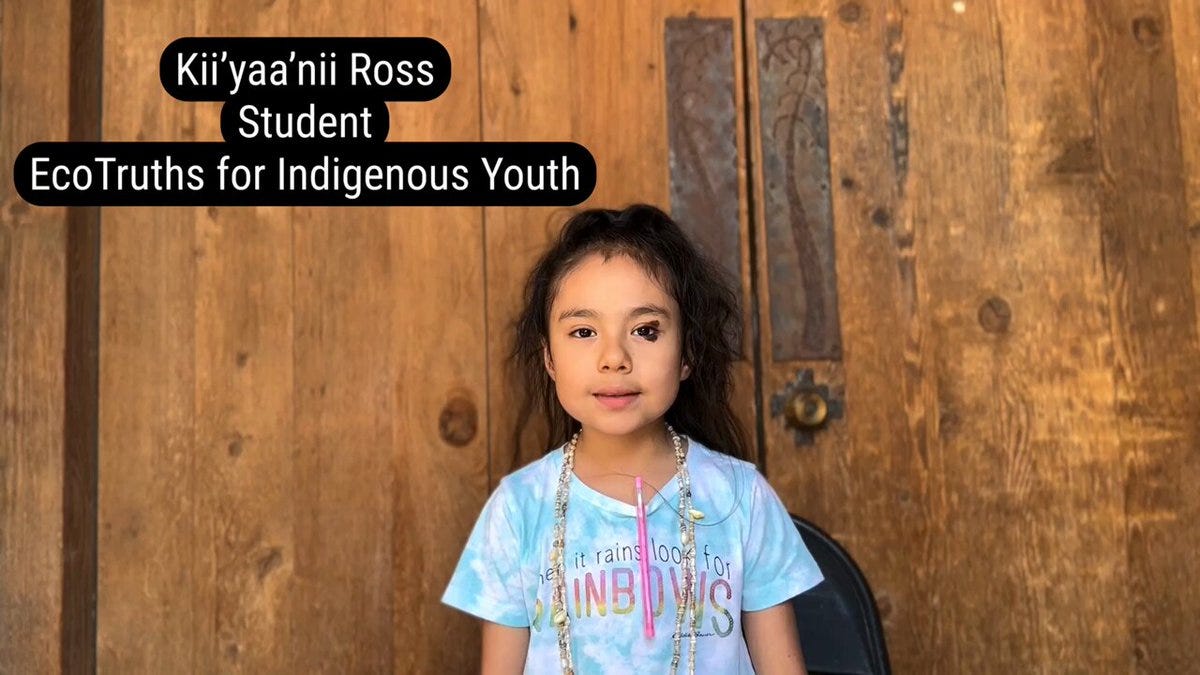

-A short article for my home publication, Arizona Luminaria, on how the latest jaguar known to be roaming southern Arizona got his name: O:ṣhad Ñu:kudam, or “Jaguar Protector” in the O’odham language.

I’ll end with a video of a truly inspiring 8-year-old Diné girl explaining why she felt it was important to give the jaguar an Indigenous name. (Click on the image to give it a watch.)