a case in a book

my book about a case — set calendars for Feb 6

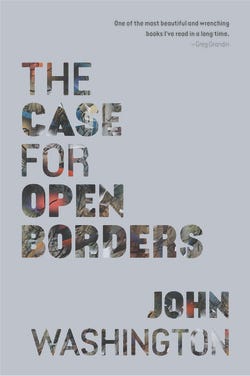

Above is the not-yet-finalized-but-close cover of my second book. (Deep thanks and much respect to artist Julie Mehretu, whose work you see poking through those letters, and whose full and stunning painting, Haka (and Riot), will be reproduced in the inside cover.) Though I advocated for keeping the title direct and simple—“The case for…”—the book both is and is not what you might expect from the cover/title.

I took a creative, historical, literary, and sometimes stylistically weird approach to the topic. And I don’t really claim that it is the case for open borders, but rather a case, and a very particular one. There’s something unconvincing, I think, especially on a bookshelf and especially on this topic, of starting with an indefinite article.

My overall aim with the project was, and remains, to add as much context to the idea of open borders as possible, bringing the subject down from what may seem a rarefied or ridiculous ideal to a digestible, grounded, and urgent case for reversing the rise of border militarization. I also wanted the book to provoke, challenge, unsettle, test, and, ultimately, push beyond boundaries. My hope, in sum, is that this book performs what it signifies.

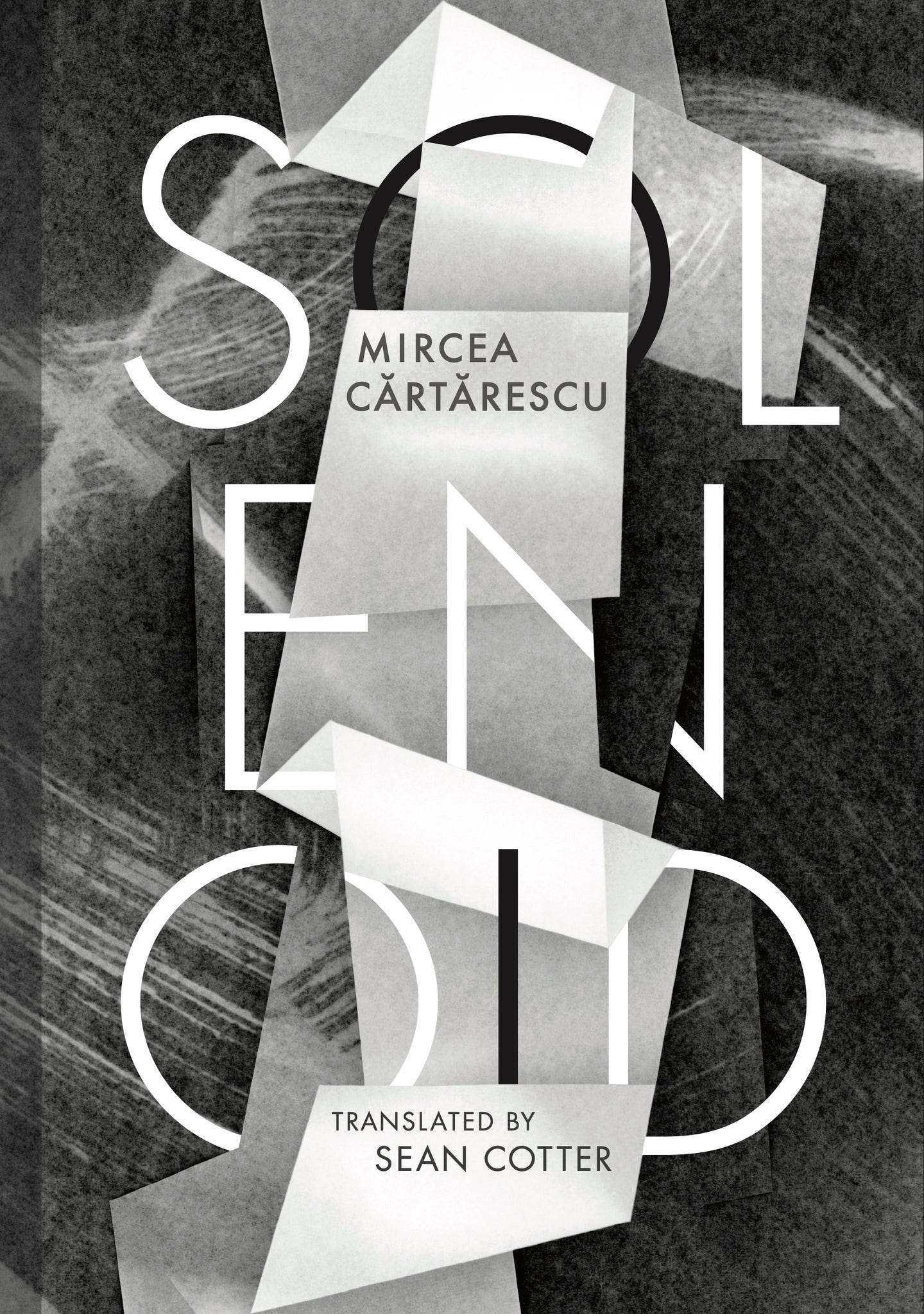

Which is, partly, why I felt so uncannily moved by Mircea Cărtărescu’s novel Solenoid, whose narrator reflects: “I have read thousands of books but never found one that was a landscape as opposed to a map.” That beautiful idea nods to something close to what linguists call performative language, words that don’t just point to concepts but effectuate or perform what they simultaneously signify. An easy example is the quasi legal utterance of “I do” in a wedding ceremony. That expression is the action itself: words wielding the hammer of language, with this grammar I thee bind.

Do I think I’ve written a landscape with The Case for Open Borders? Do I think that my book actually opens borders even as it advocates for and directs their opening?

I wish.

As passionate as I am about migrants’ rights and migrant justice, the book is not a manifesto. In spite of and in spirit of the title, I like borders.

I like the interstitial, cultural and linguistic alchemical spark that abounds at borders. I like the polyphony, blend, and clash that borders embody. What I don’t like is razor wire enisling communities, human filtering, or the immobilizing and gross exploitation of people. I don’t like the sickening mix of forced displacement and immigration controls. I don’t like the attenuation of asylum protocols, or the footloose genocidal land-grabbing of colonizers followed by their slamming of the door behind them. That clash is the spirit I try to capture in the Case for Open Borders. And I contextualize it deep in history and contemporize it with abundant reporting of people who cross, are crossed by, borders.

The stance I take is — dropping an anchor of bona fides here — based on more than a decade of reporting on immigration and border issues, talking to thousands of migrants and following very closely the grievous harms and curtailed liberties that borders beget. Ducking ideology and political fads, I’ve tried my best to take an honest, objective, phenomenological approach to the topic.

I started, before I even knew this book was a book, with basic questions: what is a border, how does a border function, what are the impacts of borders? And then I started trying to really ask those questions, to drill down, and the deeper I got, year after year, into the interrogative, the more I started working through towards an answer.

If you don’t agree with my take, or are skeptical, this is exactly the book for you. We (royally) are saturated with anti-immigration rhetoric. Even if your politics is against that malicious grain, the spirit of xenophobia sweats through the pours of society, staining us all.

There’s a pretty clear intuitive sense of the anti-immigrant extreme: sealed borders. But what about its antipode? When have you heard — rather than the term used as a smear or strawman — a clear, articulated case for open borders? Even if you continue to support at least some immigration restrictions, you would do well to understand what those advocating for free and open migration mean, what their vision is. I’d argue, and I do, that those advocating on the left for free and open migration need to better clarify their stance. That’s a big part of this project—to fill in a gaping hole of understanding about the immigration debate.

Business:

The book comes out next February 6, from Haymarket Books. It’s not too early to pre-order, directly from Haymarket, from Bookshop, or from Amazon. It’s also not too early to think about engaging with and discussing the book. If you’re an academic, an activist, a book reviewer, or in any way engaged in your community and are interested in reading/discussing a book that deeply probes the long history and current reality of borders, reach out (johnbwashington@gmail.com) and we can start scheming.

And, while I’m in promo mode, I’ll make two other quick and more general recommendations. First: buy a book. Go into a bookstore and buy a new book by a living author (double indefinite). If you don’t think you need that advice, buy another one.

I make that rec with the experience of probably not even quite breaking even on my debut book, The Dispossessed. Writing books, or writing at all, takes a lot: of effort, mental toil, obsessive honing, as well as years of experience. At the same time, we’ve been so saturated with instant information that we've come to expect it — almost as part of us, of who we are — to be immediately accessible. But such accessibility comes at a cost, to either the consumer/reader or the producer/writer. The former duo, I believe, needs to pick up more of the bill.

Which is my second recommendation: pay for your news. If you’re in Arizona, try donating to AZ Luminaria, where I work. I’ve been researching for months on another investigation into a local Tucson jail, and these stories take, besides a lot of nights and soul out of me, a lot of money out of AZ Lu. Or consider subscribing to your local daily paper. Slapping a newspaper on the kitchen table and sitting down in the morning is, IMO, one of adulthood’s most precious and elemental joys. As Hegel once said (paraphrasing here): the opening of the morning paper has replaced the morning prayer. Take a moment in the morning to connect to your community, to your god.

Solenoid:

It’s hard to put an adjective to such a massively ambitious door-stopper of a novel as Mircea Cărtărescu’s Solenoid, recently translated by Sean Cotter.

For style/theme: imagine Knausgaard meets Murakami meets Samuel Delaney meets Cormac McCarthy, and their huddle takes place in the Museum of Jurassic Technology which has a secret door in one of the corner rooms that opens to Meow Wolf, where Kafka is skittering across the ceiling above you.

The plot?

A lonely, tubercular, obsessive bookworm of a boy grows up to be a schoolteacher, except that his person kinda splits in two as a teenager when a long fever dream of a poem he wrote is panned in a writing workshop. The man then goes on exploring the bifurcated worlds of multiple dimensions, the gods of dream and possibility.

The book is set in Bucharest, “the saddest city on the face of the earth.” The protagonist lives in a ramshackle, Borgesian, infinite house situated on top of a solenoid that makes him, among other effects, levitate in his bed. In one part of his home is a dentist’s chair, below which sits a enormous plantlike organism that is nourished by pain. At one point, the man finds himself in “the night of a mite’s body” and evangelizes to a small patch of mange on a man’s hand (where millions of individual mites make up enormous colonies and intricate cities). He bears to the miniature bugs a message of another world, bridging not only the languages of mites and man, but bridging minds, dimensions, and varied universes. It is a book of insane, Boschian grotesqueries and abstruse sorta-science, full of elán and hope and love.

“No book has any meaning if it is not a Gospel,” Cărtărescu writes. “A prisoner on death row could have his cell lined with bookshelves, all wonderful books, but what he actually needs is an escape plan.”

By which I’ll turn back to my forthcoming book: not any kind of gospel, but The Case for Open Borders is very much meant to be, in whatever small way, an escape plan.

Hi John,

Enjoyed reading your thoughts behind the intention of your new book. Am looking forward to it. You touched on a lot of great conversation starters. When I went to the reach out link it was broken. 🤷🏻♀️Kate

Great statement.